Hønse-Lovisas hus

Hør om Hønse Lovisa, om hennes kjærlighet til jenter som kom i uløkka, og lausungene deres.

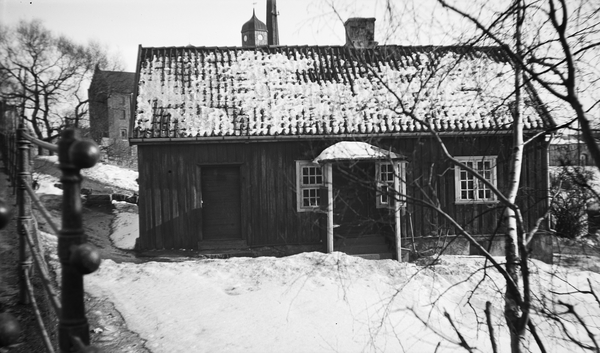

Hønse-Lovisas hus har fått sitt navn etter en skikkelse i Oskar Braatens skuespill «Ungen» fra 1911.

Hønse-Lovisa er en modig og generøs kvinne som tar seg av barna til jentene som arbeidet på fabrikkene langs elva.

Huset ble sannsynligvis satt opp som sagmesterbolig omkring 1800, og har vært både bolig for mestre og arbeidere, lager og butikk.

I falleferdig tilstand ble den tatt i bruk av kunststudenter før en forfatter satte huset i stand i samarbeid med kommunen. I dag drives stedet som en liten kulturkafé hvor historie møter diktning og samtidskunst.

Det som i dag kalles Hønse-Lovisas hus ble trolig satt opp rundt 1800 som bolig for sagmesteren på Monsesaga.

Huset er på mange måter typisk for de mange små trehusene som ble satt opp rundt sagene, møllene og etter hvert fabrikkene langs Akerselva.

Husene kunne ha mange ulike funksjoner til ulike tider, og det har også dette huset hatt. Før industrien kom var det særlig sagbrukene som dominerte ved elva.

Det lå flere sager i fossefallene ved Beierbrua. Noen av dem tilhørte familien Monsen/Matiesen på Linderud gård og ble derfor kalt Monsesagene. De drev sagbruksvirksomhet her frem til 1835.

I 1846 ble saga og den lille mesterboligen kjøpt av Christiania Tugthus og tilknyttet en kledesstampe. I en stampemølle ble vannkraften brukt til å løfte treklubber som banket eller stampet tekstiler, bark og eller annet som skulle knuses eller gjøres mykt.

På tukthuset, datidens fengsel, i Storgata, vevet fangene bl.a. ullstoffer som ble brakt opp hit for å toves til tett varmt vadmel i stampemølla.

Stampemester Engelbreckt Colberg og hans tyskfødte kone Maren Dorthea bodde i huset sammen med en møllearbeider og hans familie.

Virksomheten opphørte en gang på 1860- 70-tallet. Da ble huset brukt til arbeiderbolig, siden til lager og annet som de omkringliggende fabrikkene hadde behov for.

I adressebøker for Kristiania og Aker på begynnelsen av 1900-tallet finner så at leietaker er Madam Kaisa Olsen. Hun drev med frukt og småhandel en stund utover på 1900-tallet.

I 1936 flyttet Harald Johansen og hans familie inn. De bodde her helt frem til slutten av 1960 tallet.

Fra 1971 til 1978 var det unge kunststudenter som fant husly i det da forfalne lille trehuset ved fossen, før forfatteren Sigbjørn Hølmebakk flyttet inn med en kontrakt med byantikvaren og Oslo kommune om å sette huset i stand.

Bydel Sagene omgjorde huset til et kulturhus for nærområdet i 1993.

Oskar Braatens univers

Beierbrua er på mange måter Oskar Braatens bro. Han kalte den fabrikkjentenes bro. I oppveksten var han daglig vitne til den strie strømmen av kvinner til eller fra arbeidet i fabrikkene.

Oskar Braaten var Oslos arbeiderdikter født i 1881 og død i 1939.

Han skrev om Johnny og Mathilde i Ulvehiet, om Hønse-Lovisa og Milja og alle de andre fabrikkjentene som hadde havnet i «uløkka», om sorger og gleder i arbeiderstrøkene rundt Sagene og andre steder.

Han har fått sin byste oppsatt her, og selv bodde han oppe i Holsts gate 2 på hjørnet av Sandakerveien i det han kalte for Hjemmet.

Du ser den hvite leiegården fra brua. Her vokste han opp med søsteren og moren. I 1928 skrev Braaten: At det ikke finnes noen mer bediktet gatestump i Oslo by enn Sandakerveien fra Beierbroen og opp til Thorshauggaten, tror jeg nok jeg tør si.

Oskar Braaten: Fra mine gutteår på Sagene (1929): Men livet var (nå) ikke bare skole og lek, vi hadde da litt nyttig å pusle med også, vi hadde for eksempel matspannene. Matspannene, spør De? Ja, matspannene! Middagshvilen på fabrikkene varte bare en time, og det var ikke alle som brydde seg om å gå hjem i den korte tiden.

Det var ungkarer og barnløse som ingenting hadde hjemme å gjøre, og det var mange som bodde langt unna. Og da måtte de jo ty til matspannene og kokekonene. Vi hadde minst én i hver gate, vi hadde én i «Hjemmet» og vi hadde én lenger oppe i Sandakerveien.

Tidlig på formiddagen begynte de å koke i digre kar, klokken tolv stod de fulle spannene i rekke og rad i entréen deres og helt ut i trappen. Spannene var delt i to, den underste delen var til suppe, den øverste til «ettermat», de var heftet sammen med en rem til å bære i. Og så var det å ta disse spannene og løpe ned til «Sømmen» og «Hjula» og «Gråh».

I førsten greide vi ikke å få med oss flere enn et par spann i hver hånd, men vi øvde oss opp og ble flinkere og flinkere. De likeste av oss kunne spurte nedover gaten med en åtte-ti spann uten å slå ut en dråpe.

Og nede i forhallen på fabrikkene satte vi spannene fra oss og fløi av går de etter nye. Hver kokekone hadde kjennemerke på spannene sine, og alt gikk bra. Det verket nok litt i armene når sjauen var over, men vi tjente penger. Vi hadde ti øre uken for hvert spann. Og det ble jo en liten skilling. Og det kunde være godt å få lagt noen kroner til side til konfirmasjonen.

Beierbrua – fabrikkjentenes bru

Trebrua over elva ved Hønse-Lovisas hus er en av de eldste broene.

Den har navn etter eier i 1671, skredder Anders Beyer. Første brua var en enkel gangbro, men i 1837 ble den utvidet til kjørebro. Utover på 1900-tallet trillet det biler her også, men i 1974 brant broa. Da ble den restaurert tilbake til 1837-utgaven av seg selv, og er nå kun gangbro igjen.

Akerselva – et museum gjennom byen

Akerselva er verdt en vandring. Enten om du tar en sving nedenom eller setter av noen timers frisk gange tvers gjennom byen langs hele elvas drøyt 8 kilometer, så får du deg en naturopplevelse, kanskje en aha-opplevelse, og du får kjenne Oslo rett på hovedpulsåren.

En vandring langs elva gir mulighet for å lese og oppleve vår egen historie. I Europeisk sammenheng er Akerselvas industrihistoriske landskap helt unikt og svært verdifullt av mange grunner. Akerselva er den eneste typiske industri-elv som renner tvers gjennom hovedstad med start og slutt innenfor bygrensene.

Elva er helt spesiell i representasjon av ulike industrigrener og tidsepoker. Her er 1700 tallets industribygg av tre, her er 1800-tallets typiske fabrikker av rød murstein med jernsprossede vinduer, shed-tak og høye murte fabrikkpiper, og her er moderne industribygg fra industrialismens senere faser og dagens eksisterende industri.

Her er bevarte miljøer av arbeiderboliger fra ulike epoker. Her er mange spor av teknisk infrastruktur med demninger, broer, rørgater og dammer. Gjenbruk av industriområdene til nye formål er typiske og godt egnet til å studere avindustrialiseringsprosesser og gjenbruk av storbyers industriområder.

Elva er tilrettelagt med turstier og parkanlegg, museer og andre institusjoner som bevarer og formidler industrihistorien, og kafeer og kulturtilbud langs hele elva fra Kjelsås til Bjørvika.

Vi ønsker at alle som bor i Oslo og besøker Oslo skal få oppleve Akerselvas unike kulturminnelandskap i det som er et sammenhengende utemuseum gjennom byen. God tur!

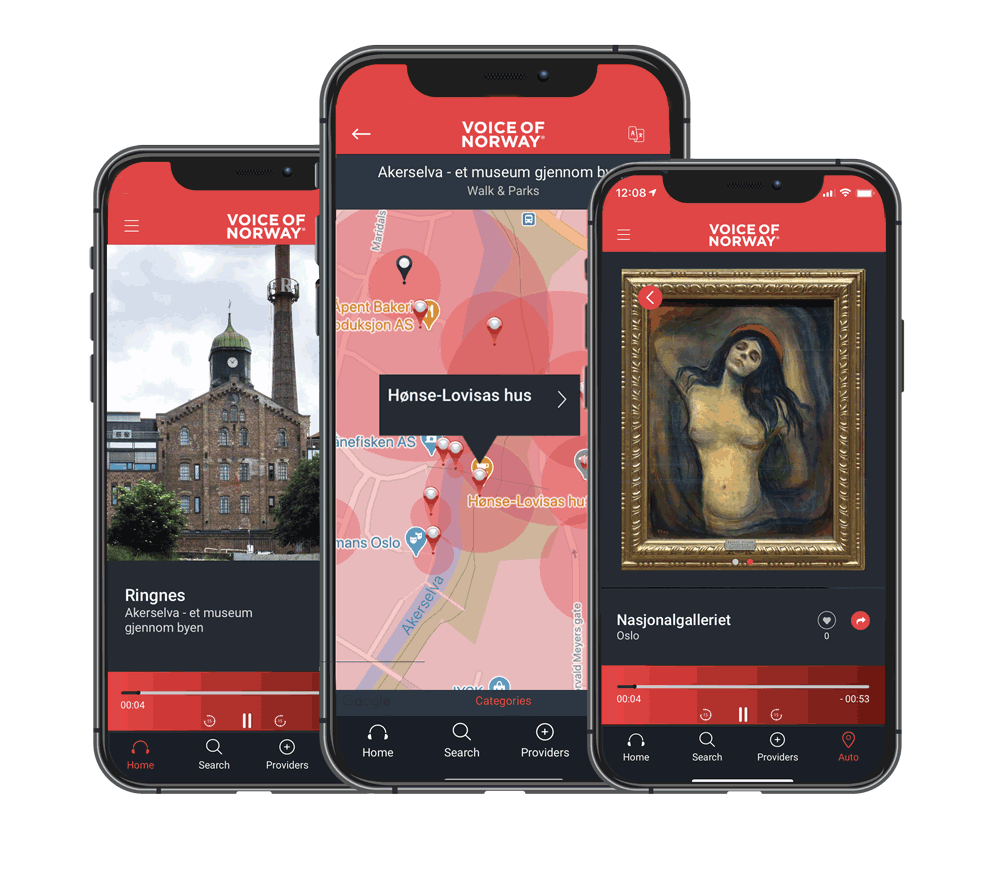

Akerselva - et museum gjennom byen

Hør industrihistoriene lang Akerselva, 94 historier er samlet her.

Vandring gjennom Oslo

Innblikk i 40 nye og gamle historier fra Oslo; bygninger, krigshistorier, Vigelandsparken, Nasjonalgalleriet.

Ta kontakt med oss for å få vite mer om hvordan du kan legge til rette for denne typen formidling i din region eller område!

Team Voice Of Norway

Telefon: 94096772